Tangible helps track, manage, and report on embodied carbon throughout the development process.

Article by Emily Flynn, Founding Researcher at Tangible

Illustrations by Farah Assir, Designer at Tangible

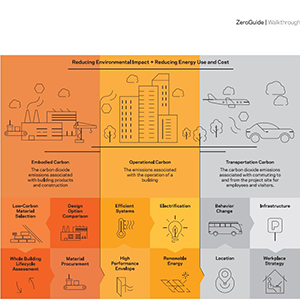

Over the past few decades, building performance in North America has improved largely as a result of building codes. The opportunity for impact is substantial, as buildings account for almost 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions, of which building operations make up 27% and building materials such as concrete and steel make up 11% (this is also known as embodied carbon). To date, the industry has mostly focused on improving the operational performance of buildings. Since the introduction of building energy efficiency measures in the 1970s, there has been a groundswell of operational energy code requirements for buildings at the national, state, and local level.

Today, most US states and Canadian provinces have adopted building energy codes. These codes set the minimum standards for operational efficiency for new buildings constructed within that state. Since the first version of ASHRAE 90.1 (a prominent energy code) was published in 1975, commercial buildings have become ~50% more efficient. The Department of Energy estimates that between 2010 and 2040 energy codes will reduce CO2 emissions from U.S. commercial and residential buildings by 900,000,000 metric tonnes (and save $138 billion in energy costs). It’s clear that over the last 40 years building codes have played a large role in achieving significant energy and carbon reductions across building operations. Now the industry is turning its sights to embodied carbon.

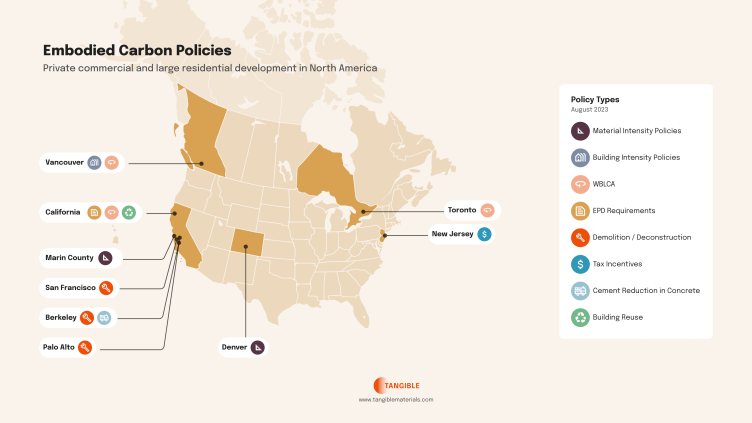

Embodied carbon considerations have only recently been incorporated into building codes and policies in North America. Among the first policies to pass was Buy Clean California, a public procurement policy, which was voted into law in 2017. Since then, the landscape of public- and private-sector policies has rapidly expanded. Many public policies have been enacted that introduce embodied carbon requirements for municipal, state, and national construction projects. However, we will solely focus on policies that impact private commercial and large multifamily development.

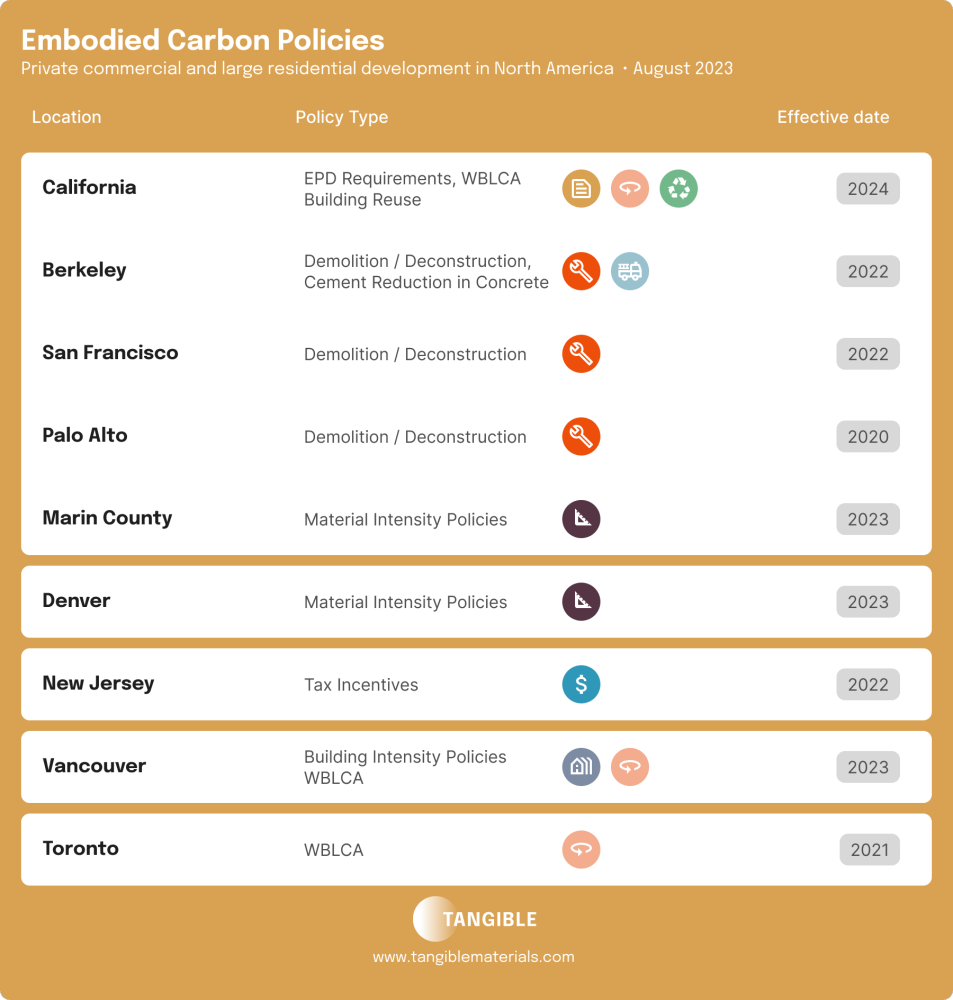

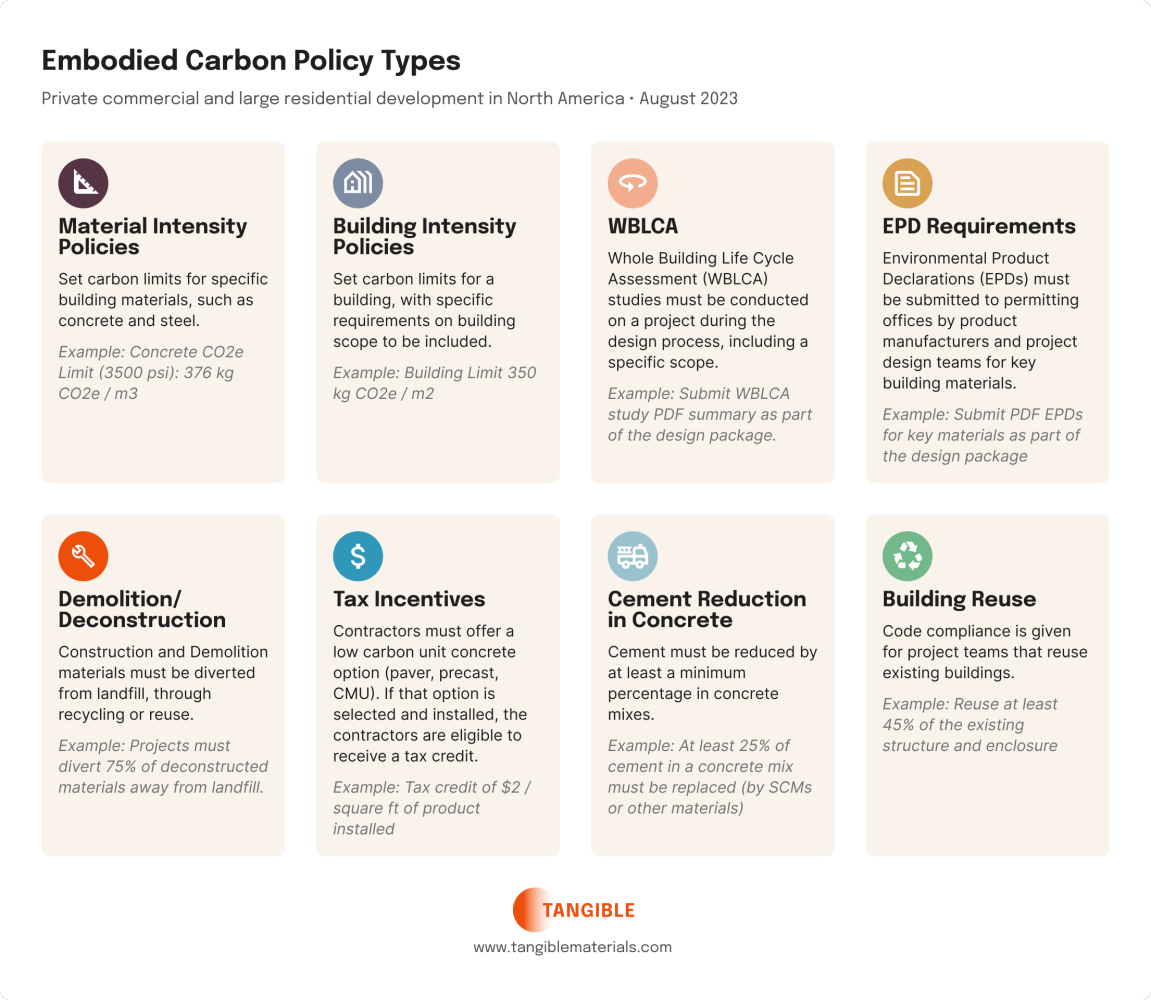

In the table below, we’ve highlighted 11 embodied carbon policies throughout North America that apply to private commercial and large multifamily developments. We’ve categorized these policies into eight discrete types: material intensity policies, building intensity policies, Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) requirements, Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment (WBLCA), demolition / deconstruction, tax incentives, cement reduction in concrete, and building reuse. These policies affect private construction throughout California, as well as construction in Toronto, Vancouver, New Jersey, and Denver.

Current embodied carbon policy requirements affecting private sector development:

All of these policies are actively in effect, so construction projects happening today in these jurisdictions need to comply with these requirements. The exception is California’s CALGreen, where compliance begins in 2024. Projects could be at risk of not receiving their construction permit if they are not in compliance with these requirements.

Although it may seem like a wide range of embodied carbon policies have been enacted, two main typologies are starting to form. These typologies are Prescriptive requirements–mandatory measures that buildings must follow–and Performance requirements–buildings must show they are performing better than an “average” building. These typologies are firmly established within operational carbon policies and are widely recognized in the industry.

Most embodied carbon policies affecting private development today are Prescriptive requirements (i.e. mandatory measures). Examples include:

- Concrete and steel products cannot exceed maximum carbon emission limits specified in the building code.

- Buildings have an embodied carbon budget based on the total floor area of the project.

- Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) are required to be submitted on projects for key materials.

- Buildings must be deconstructed as opposed to mechanically demolished (a.k.a. bulldozed), so building materials can more easily be reused on other projects.

We’re also starting to see embodied carbon Performance requirements. Performance pathways allow for design flexibility and creative problem solving, but they also require data. Performance pathways are made possible through extensive research to understand what a reasonable baseline is, and what a reasonable reduction below that baseline would be. Nonprofits like the Carbon Leadership Forum and AIA 2030 Design Data Exchange have open calls to submit embodied carbon studies to continue to improve industry knowledge of typical embodied carbon emissions at the building level. Current examples of Performance requirements include:

- In Vancouver, buildings will need to show a 10-20% reduction below baseline starting in 2025.

- The newly approved California Green Building Code (CALGreen) specifies a 10% reduction below baseline as one path to compliance starting in 2024.

Looking ahead, there are many proposed embodied carbon policies that could affect private development. Two bills have been moving through the California legislature during the 2023 legislative session—the Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB 253) and the Climate-Related Financial Risk Act (SB 261)—which both include emissions disclosure requirements that would likely include embodied carbon for building owners and developers. And in Toronto, experts have suggested that the current embodied carbon limit of 350 kg CO2e / m2 for public construction could be expanded to private development in the next code cycle, coming into effect in 2025.

There are many questions the industry will need to address as embodied carbon policies continue to evolve, but we expect the landscape of policies to grow each year. Just like with operational carbon, building codes will likely be a key lever in accelerating awareness and adoption of low-carbon building strategies. The industry is taking key steps to address the challenge of embodied carbon through the power of building codes.

What embodied carbon policies are we missing? Reach out and let us know.

This summary is based on the following embodied carbon building code requirements, affecting private commercial and large multifamily development in North America: California AB 2446 and CALGreen 2022 Intervening Cycle, City of Berkeley Green Building Requirements Sections 4.405.1 and 4.408.1, San Francisco Construction and Demolition Debris Recovery Law City Ordinance No. 144-21, Palo Alto Municipal Code Section 5.24, Marin County Code Section 19.07, Denver Building Code Section 901.3.2.1 and Section 901.3.2.2, New Jersey Senate Bill 3091, Vancouver Building By-laws, and Toronto Green Building Requirements.

Tangible manages embodied carbon across portfolios, enabling companies to:

- Measure impact over-time by comparing projects to targets

- Take action through early-stage planning and product recommendations

- Report on portfolios or individual projects instantly to meet corporate and regulatory standards

Emily Flynn

Farah Assir

Although it may seem like a wide range of embodied carbon policies have been enacted, two main typologies are starting to form. These typologies are Prescriptive requirements–mandatory measures that buildings must follow–and Performance requirements–buildings must show they are performing better than an “average” building. These typologies are firmly established within operational carbon policies and are widely recognized in the industry.